“Marketers want to make better decisions.” A phrase I use in almost all of my presentations. But after reading Thinking, Fast and Slow by Nobel Memorial Prize in Economics winner Daniel Kahneman, I am once more reminded of the fact that the right decision or a better decision is not always easy. Why? Because humans are not easy to understand. We are not rational.

Still in today’s marketing approach we talk about a 360 degree view of the customer. How can we achieve that, if the human being cannot even explain it’s own thoughts?

Easy numerical example: a bat and a ball cost $1,10. The bat costs $1 more then the ball. How much does the bat cost? Think about what comes to your mind. A lot of 1es and 10es, right? Making it hard to find the solution.

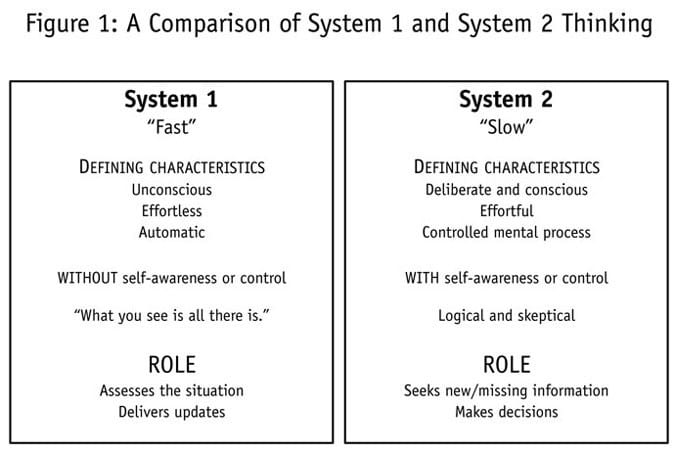

As Kahneman points out, we are driven by cognitive biases and make cognitive errors quite often. His systems of fast and slow thinking are described below:

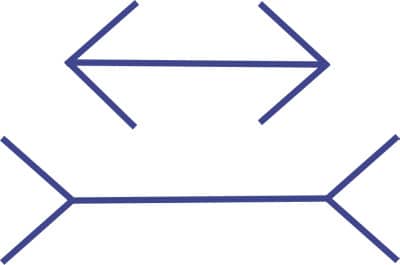

Take the famous example below. You may know that both lines are of the same length (System 2), but you cannot unsee that one seems longer (System 1)…

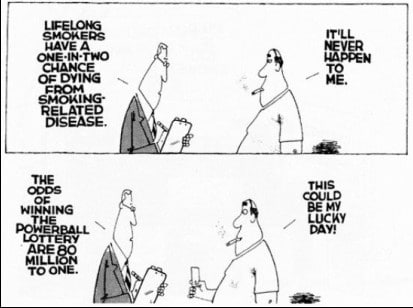

If you are a marketer however, you have to deal with often not very rational behaviours from your customers and of course your own errors and biases as well. Having worked for a gambling company in Austria I have learnt that humans tend to over believe probability to gain something and underestimate it at the same time.

Kahneman for instance quotes a couple of research outcomes showing that people who spend their time, and earn their living, studying a particular topic produce poorer predictions than dart-throwing monkeys. In a lot of research cases it is shown that the accuracy of experts was matched or exceeded by a simple algorithm.

Sometimes this simplification can also lead to interesting outcomes, like the formula for marital stability: “frequency of lovemaking minus frequency of quarrels.”

In a memorable story in their book SuperFreakonomics, Steven Levitt and Stephen J. Dubner describe how banking data was used to find possible terrorists in the UK. Designing an algorithm using a number of different variables to identify potential terrorists based on banking habits. For instance, terrorists are highly unlikely to have a savings account, buy life insurance, or withdraw from an ATM on a Friday afternoon. The last habit is due to the fact that Muslims have mandatory prayer services every Friday. This system was able to identify about 30 potential terrorists out of millions of bank customers. At the same time however, a 99% accurate algorithm would still falsely identify about 80,000 potential terrorists out of a bigger dataset of let’s say 8 million people. It is also not disclosed what was variable X in the banking data that made the algorithm that good.

In marketing we are facing the same challenges. How do we find the opportunities in the data? How do we identify the right customers at the right time to engage with them?

Enter Ginni Rometty’s discussion at the Gartner Symposium announcing the cognitive era.

Now humour me for a second and think about the future possibilities when cognitive systems improve our decision making process – also in marketing. Below is an example of Watson Personality Insights that can already be linked to the IBM Marketing solutions today. It provides additional insights on the customers we deal with and tries to help the marketer make better decisions. A customer is not only a segment anymore. We try to factor in personality.

Results of IBM Interact’s self learning capability for instance have proven over and over again that it can help in better targeting. So why not trust machines a little more? Bringing cognitive capabilities and marketing capabilities together can only be valuable. I am all for it.

Results of IBM Interact’s self learning capability for instance have proven over and over again that it can help in better targeting. So why not trust machines a little more? Bringing cognitive capabilities and marketing capabilities together can only be valuable. I am all for it.

Last but not least: read those books!